Resources

Webinars

SVB: A Warning of Financial Resilience

Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse is a warning for CFOs and finance leaders who are not able to offer immediate, real-time questions on impacts to their balance sheets, income statements and cash flow.

-

Filter by type

-

Filter by products

-

Success Stories, VideosBreak Free from Liquidity GridlockOur clients will tell you, they love Kyriba. Organizations from many industries and of various sizes have embraced Kyriba for real-time cash visibility, increased operational efficiency, and all enterprise liquidity management needs.Read the success story

Success Stories, VideosBreak Free from Liquidity GridlockOur clients will tell you, they love Kyriba. Organizations from many industries and of various sizes have embraced Kyriba for real-time cash visibility, increased operational efficiency, and all enterprise liquidity management needs.Read the success story -

VideosElevate Your Forecasting CapabilitiesIn the complex world of global finance, managing liquidity can feel like an uphill battle. Without complete data and automation, navigating a web of banking relationships becomes daunting.Watch the video

VideosElevate Your Forecasting CapabilitiesIn the complex world of global finance, managing liquidity can feel like an uphill battle. Without complete data and automation, navigating a web of banking relationships becomes daunting.Watch the video -

VideosEmpowering Global Bank Connectivity, Unleashing PotentialFind out how Kyriba’s global bank connectivity solution can help you break free from fragmented data, siloed systems, and disconnected workflows.Watch the video

VideosEmpowering Global Bank Connectivity, Unleashing PotentialFind out how Kyriba’s global bank connectivity solution can help you break free from fragmented data, siloed systems, and disconnected workflows.Watch the video -

VideosData Security in an Age of UncertaintyIn the complex world of global finance, managing liquidity can feel like an uphill battle. Without complete data and automation, navigating a web of banking relationships becomes daunting.Watch the video

VideosData Security in an Age of UncertaintyIn the complex world of global finance, managing liquidity can feel like an uphill battle. Without complete data and automation, navigating a web of banking relationships becomes daunting.Watch the video -

VideosOptimize Liquidity with KyribaIn the complex world of global finance, managing liquidity can feel like an uphill battle. Without complete data and automation, navigating a web of banking relationships becomes daunting.Watch the video

VideosOptimize Liquidity with KyribaIn the complex world of global finance, managing liquidity can feel like an uphill battle. Without complete data and automation, navigating a web of banking relationships becomes daunting.Watch the video -

WebinarsManaging FX Risk In Complicated Market ConditionsAre you ready to navigate the complexities of FX risk in today's uncertain market conditions? Join us for an insightful webinar hosted by Andy Gage, SVP of FX Sales and Advisory Services at Kyriba. Dive deep into the strategies and tools essential for finance professionals in 2024. Don't miss this opportunity to gain expert insights and practical solutions tailored to today's financial landscape.View Recording

WebinarsManaging FX Risk In Complicated Market ConditionsAre you ready to navigate the complexities of FX risk in today's uncertain market conditions? Join us for an insightful webinar hosted by Andy Gage, SVP of FX Sales and Advisory Services at Kyriba. Dive deep into the strategies and tools essential for finance professionals in 2024. Don't miss this opportunity to gain expert insights and practical solutions tailored to today's financial landscape.View Recording -

WebinarsElevating Working Capital: Strategy for Growth and Resilience in Uncertain TimesIn this dynamic era, where market conditions evolve and opportunities for growth emerge, Kyriba is excited to offer a concise webinar aimed at equipping your business with the insights and tools needed to enhance your working capital.View Recording

WebinarsElevating Working Capital: Strategy for Growth and Resilience in Uncertain TimesIn this dynamic era, where market conditions evolve and opportunities for growth emerge, Kyriba is excited to offer a concise webinar aimed at equipping your business with the insights and tools needed to enhance your working capital.View Recording -

Fact SheetsKyriba Open Formats StudioThe Kyriba Open Formats Studio (OFS) offers a complete set of self-service tools to quickly implement, test and deploy payment formats within the Kyriba Payment Hub.Read the fact sheet

Fact SheetsKyriba Open Formats StudioThe Kyriba Open Formats Studio (OFS) offers a complete set of self-service tools to quickly implement, test and deploy payment formats within the Kyriba Payment Hub.Read the fact sheet -

WebinarsNavigating the Financial Horizon: Mastering Forecasting & Liquidity PlanningWednesday, March 06, 2024 | 12 PM CET | Join us on-demand for an exclusive Kyriba Webinar. Dive into the art and science of financial forecasting and liquidity planning in today's volatile market.View Recording

WebinarsNavigating the Financial Horizon: Mastering Forecasting & Liquidity PlanningWednesday, March 06, 2024 | 12 PM CET | Join us on-demand for an exclusive Kyriba Webinar. Dive into the art and science of financial forecasting and liquidity planning in today's volatile market.View Recording -

Fact SheetsKyriba Open Reports StudioKyriba Open Reports Studio is a powerful Excel add-in that seamlessly integrates with the Kyriba application via Kyriba APIs to empower finance professionals in treasury, accounting and other functions to take control of their data.Read the fact sheet

Fact SheetsKyriba Open Reports StudioKyriba Open Reports Studio is a powerful Excel add-in that seamlessly integrates with the Kyriba application via Kyriba APIs to empower finance professionals in treasury, accounting and other functions to take control of their data.Read the fact sheet -

Success StoriesWorld Vision Revolutionizes Treasury Processes to Maximize Global ImpactsAs a global Christian relief, development, and advocacy organization World Vision helps children, families, and communities overcome poverty and injustice, irrespective of religion, race, ethnicity, or gender.Read the success story

Success StoriesWorld Vision Revolutionizes Treasury Processes to Maximize Global ImpactsAs a global Christian relief, development, and advocacy organization World Vision helps children, families, and communities overcome poverty and injustice, irrespective of religion, race, ethnicity, or gender.Read the success story -

Success Stories, VideosFrom our Clients: Why We Love KyribaOur clients will tell you, they love Kyriba. Organizations from many industries and of various sizes have embraced Kyriba for real-time cash visibility, increased operational efficiency, and all enterprise liquidity management needs.Read the success story

Success Stories, VideosFrom our Clients: Why We Love KyribaOur clients will tell you, they love Kyriba. Organizations from many industries and of various sizes have embraced Kyriba for real-time cash visibility, increased operational efficiency, and all enterprise liquidity management needs.Read the success story -

Research, Currency Impact ReportsKyriba’s February 2024 Currency Impact ReportThe February 2024 Kyriba Currency Impact Report analyzes the reported effects of currencies on North American and European companies during Q3/23.Read the Report

Research, Currency Impact ReportsKyriba’s February 2024 Currency Impact ReportThe February 2024 Kyriba Currency Impact Report analyzes the reported effects of currencies on North American and European companies during Q3/23.Read the Report -

Success StoriesTreasury System Integration Leads Primoris Towards M&A SuccessAlexion works to transform the lives of people affected by rare diseases and devastating conditions by continuously innovating to push the boundaries of medicine, technology, and healthcare services.Read the success story

Success StoriesTreasury System Integration Leads Primoris Towards M&A SuccessAlexion works to transform the lives of people affected by rare diseases and devastating conditions by continuously innovating to push the boundaries of medicine, technology, and healthcare services.Read the success story -

Success StoriesKuala Lumpur Kepong Berhad (KLK) Revolutionises Treasury Management Processes with KyribaKuala Lumpur Kepong Berhad (“KLK”) started as a plantation company in 1906 and until today, the development of oil palm and rubber remains the Group’s core business. KLK presently has about 300,000 hectares of planted area (97% oil palm). Our land bank is spread across Malaysia (Peninsular and Sabah), Indonesia (Belitung Island, Sumatra, as well as Kalimantan) and Liberia.Read the success story

Success StoriesKuala Lumpur Kepong Berhad (KLK) Revolutionises Treasury Management Processes with KyribaKuala Lumpur Kepong Berhad (“KLK”) started as a plantation company in 1906 and until today, the development of oil palm and rubber remains the Group’s core business. KLK presently has about 300,000 hectares of planted area (97% oil palm). Our land bank is spread across Malaysia (Peninsular and Sabah), Indonesia (Belitung Island, Sumatra, as well as Kalimantan) and Liberia.Read the success story -

WebinarsAPAC 2024 Treasury TrendsTuesday, February 27, 2024 | 12:30 pm SGT | As 2024 begins, significant disruptions are evident, marked by ongoing conflicts in Europe and the Middle East, and central banks raising borrowing costs.View Recording

WebinarsAPAC 2024 Treasury TrendsTuesday, February 27, 2024 | 12:30 pm SGT | As 2024 begins, significant disruptions are evident, marked by ongoing conflicts in Europe and the Middle East, and central banks raising borrowing costs.View Recording -

Success StoriesExpanding Alexion’s Forecasting HorizonIn the pursuit of transforming the lives of people affected by rare diseases and devastating conditions, Alexion stands at the forefront of innovation, ceaselessly pushing the boundaries of medicine, technology, and healthcare services.Read the success story

Success StoriesExpanding Alexion’s Forecasting HorizonIn the pursuit of transforming the lives of people affected by rare diseases and devastating conditions, Alexion stands at the forefront of innovation, ceaselessly pushing the boundaries of medicine, technology, and healthcare services.Read the success story -

WebinarsNavigating Tomorrow: Insights for Treasurers in 2024 & BeyondThursday, February 15, 2024 | 2 PM GMT | In this exclusive webinar, we take a look into the challenges and opportunities that lie ahead for treasurers in these complex times.View Recording

WebinarsNavigating Tomorrow: Insights for Treasurers in 2024 & BeyondThursday, February 15, 2024 | 2 PM GMT | In this exclusive webinar, we take a look into the challenges and opportunities that lie ahead for treasurers in these complex times.View Recording -

WebinarsTop 5 Treasury Practices That Will Change Your 2024Tuesday, February 27, 2024 | 2 PM EST | In this webinar, hear from Kyriba clients what their transformation priorities are – and what practices they are implementing this year.View Recording

WebinarsTop 5 Treasury Practices That Will Change Your 2024Tuesday, February 27, 2024 | 2 PM EST | In this webinar, hear from Kyriba clients what their transformation priorities are – and what practices they are implementing this year.View Recording -

Success StoriesTreasury Technology Breakthroughs with Clearsulting PartnershipClearsulting’s partnership with Kyriba offers a comprehensive suite of services designed to elevate your treasury function.Read the success story

Success StoriesTreasury Technology Breakthroughs with Clearsulting PartnershipClearsulting’s partnership with Kyriba offers a comprehensive suite of services designed to elevate your treasury function.Read the success story -

Webinars2024 Cash Forecasting EssentialsThursday, January 25, 2024 | 1 PM EST | Find out everything you need to know about perfecting your cash forecasting in 2024 as a treasurer.View Recording

Webinars2024 Cash Forecasting EssentialsThursday, January 25, 2024 | 1 PM EST | Find out everything you need to know about perfecting your cash forecasting in 2024 as a treasurer.View Recording -

Research, Currency Impact ReportsKyriba’s November 2023 Currency Impact ReportThe November 2023 Kyriba Currency Impact Report analyzes the reported effects of currencies on North American and European companies during Q2/23.Read the Report

Research, Currency Impact ReportsKyriba’s November 2023 Currency Impact ReportThe November 2023 Kyriba Currency Impact Report analyzes the reported effects of currencies on North American and European companies during Q2/23.Read the Report -

Webinars2024 Treasury Trends2023 is coming to a close with notable upheaval. Significant wars continue in Europe and the Middle East; central banks have increased borrowing costs to the highest rate in well over a decade; inflation has pulled back from the peak but remains above targets; borrowing costs and access to capital have tightened; FX risks remain elevated; and many CFOs are exhibiting increased caution.View Recording

Webinars2024 Treasury Trends2023 is coming to a close with notable upheaval. Significant wars continue in Europe and the Middle East; central banks have increased borrowing costs to the highest rate in well over a decade; inflation has pulled back from the peak but remains above targets; borrowing costs and access to capital have tightened; FX risks remain elevated; and many CFOs are exhibiting increased caution.View Recording -

Fact SheetsKyriba API Integration for Microsoft Dynamics 365Kyriba’s API integration for Microsoft Dynamics 365 (D365) accelerates payments and bank connectivity projects, eliminates project risk and drastically reduces connectivity costs. The Kyriba D365 integration centralizes payment activity, fully manages bank connectivity and delivers superior fraud detection and visibility. It also provides a full suite of out-of-the-box ERP workflows for cash management, GL reconciliation, GL export, FX balance sheet and bank statement export.Read the fact sheet

Fact SheetsKyriba API Integration for Microsoft Dynamics 365Kyriba’s API integration for Microsoft Dynamics 365 (D365) accelerates payments and bank connectivity projects, eliminates project risk and drastically reduces connectivity costs. The Kyriba D365 integration centralizes payment activity, fully manages bank connectivity and delivers superior fraud detection and visibility. It also provides a full suite of out-of-the-box ERP workflows for cash management, GL reconciliation, GL export, FX balance sheet and bank statement export.Read the fact sheet -

Success StoriesKeyloop Drives Forward with Automated TreasuryWithin the vast auto retail landscape, Keyloop stands out, delivering software solutions to 16,000 dealer sites and serving most automotive manufacturers in over 90 countries. Yet, like many industry leaders, Keyloop confronted operational challenges. Specifically, their treasury team grappled with manual tasks that limited efficiency and potential growth, highlighting the need for an automated treasury management solution.Read the success story

Success StoriesKeyloop Drives Forward with Automated TreasuryWithin the vast auto retail landscape, Keyloop stands out, delivering software solutions to 16,000 dealer sites and serving most automotive manufacturers in over 90 countries. Yet, like many industry leaders, Keyloop confronted operational challenges. Specifically, their treasury team grappled with manual tasks that limited efficiency and potential growth, highlighting the need for an automated treasury management solution.Read the success story -

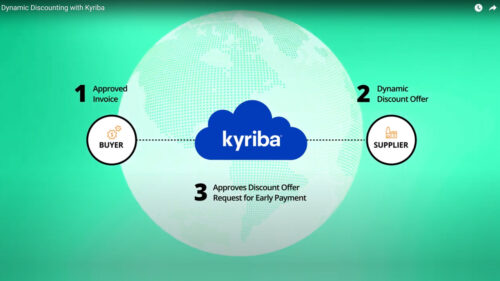

Fact SheetsKyriba Working Capital White Label Solutions for Financial InstitutionsNow more than ever, CFOs and senior finance leaders are turning to working capital solutions to optimize liquidity and generate free cash flow. With the demand continuing to grow, so do the market options.Read the fact sheet

Fact SheetsKyriba Working Capital White Label Solutions for Financial InstitutionsNow more than ever, CFOs and senior finance leaders are turning to working capital solutions to optimize liquidity and generate free cash flow. With the demand continuing to grow, so do the market options.Read the fact sheet -

Success StoriesNVA, FAH and Oracle Cerner: Treasury Success with Elire and KyribaElire, in synergy with Kyriba, is redefining financial process optimization. With a legacy spanning over 18 years, Elire has spearheaded treasury transformation projects, offering cutting-edge tools. As a Kyriba Platinum Plus Partner, Elire amplifies the essence of modern treasury.Read the success story

Success StoriesNVA, FAH and Oracle Cerner: Treasury Success with Elire and KyribaElire, in synergy with Kyriba, is redefining financial process optimization. With a legacy spanning over 18 years, Elire has spearheaded treasury transformation projects, offering cutting-edge tools. As a Kyriba Platinum Plus Partner, Elire amplifies the essence of modern treasury.Read the success story -

Success StoriesHow Varsity Brands Achieved >90% Forecasting AccuracyVarsity Brands faced numerous challenges in its treasury processes, such as limited cash visibility, disjointed cash flow forecasts and a patchwork of manual processes. Recognizing these challenges, Varsity Brands selected Kyriba to redefine and optimize their treasury operations for the future.Read the success story

Success StoriesHow Varsity Brands Achieved >90% Forecasting AccuracyVarsity Brands faced numerous challenges in its treasury processes, such as limited cash visibility, disjointed cash flow forecasts and a patchwork of manual processes. Recognizing these challenges, Varsity Brands selected Kyriba to redefine and optimize their treasury operations for the future.Read the success story -

WebinarsThe Future of Forecasting: How to Meet the CFOs ObjectivesCFOs no longer need a cash forecast…they need more! CFOs are under immense pressure to meet free cash flow targets, especially in a high-interest-rate environment, where every decision matters. That’s why real-time, actionable insights have become the lifeline for proactive liquidity management across the enterprise.View Recording

WebinarsThe Future of Forecasting: How to Meet the CFOs ObjectivesCFOs no longer need a cash forecast…they need more! CFOs are under immense pressure to meet free cash flow targets, especially in a high-interest-rate environment, where every decision matters. That’s why real-time, actionable insights have become the lifeline for proactive liquidity management across the enterprise.View Recording -

WebinarsBeyond Cash Forecasting: Rethinking LiquidityAs a companion to the newly released Executive Guide on “Rethinking Liquidity Planning to Manage the Cash Lifecycle”, this webinar will focus on how Liquidity planning differs from cash forecasting.View Recording

WebinarsBeyond Cash Forecasting: Rethinking LiquidityAs a companion to the newly released Executive Guide on “Rethinking Liquidity Planning to Manage the Cash Lifecycle”, this webinar will focus on how Liquidity planning differs from cash forecasting.View Recording -

WebinarsThe Liquidity Pulse – How Recent Geopolitical Upheavals Impact Risk and Working CapitalIn today's interconnected world, geopolitical events can send shockwaves through global businesses, profoundly affecting their risk profiles and working capital. Join us for this edition of "The Liquidity Pulse" series as we bring together industry experts to dissect the real business implications of recent geopolitical upheavals and discuss potential solutions.View Recording

WebinarsThe Liquidity Pulse – How Recent Geopolitical Upheavals Impact Risk and Working CapitalIn today's interconnected world, geopolitical events can send shockwaves through global businesses, profoundly affecting their risk profiles and working capital. Join us for this edition of "The Liquidity Pulse" series as we bring together industry experts to dissect the real business implications of recent geopolitical upheavals and discuss potential solutions.View Recording -

FAQsWhat is SEPA Payment?What is SEPA Payment? What Are the Different SEPA Schemes? How Kyriba Supports SEPA Payments?Read More

FAQsWhat is SEPA Payment?What is SEPA Payment? What Are the Different SEPA Schemes? How Kyriba Supports SEPA Payments?Read More -

eBooks, Thought LeadershipExecutive Insights: Managing FX Risk Under Daily vs. Single RateThis Executive Insights ebook covers the key differentiators between Daily and Single rate.Read the eBook

eBooks, Thought LeadershipExecutive Insights: Managing FX Risk Under Daily vs. Single RateThis Executive Insights ebook covers the key differentiators between Daily and Single rate.Read the eBook -

WebinarsAPIs Unleashed: Everything You Need to Know About APIs for Treasury and PaymentsIn this session, Celent’s embedded finance and API research leader and Kyriba will demystify APIs, talk about their value for payments, intra-day liquidity, ERP integration, fraud detection, reporting, data analysis, and so much more.View Recording

WebinarsAPIs Unleashed: Everything You Need to Know About APIs for Treasury and PaymentsIn this session, Celent’s embedded finance and API research leader and Kyriba will demystify APIs, talk about their value for payments, intra-day liquidity, ERP integration, fraud detection, reporting, data analysis, and so much more.View Recording -

Fact SheetsKyriba Oracle Cloud API IntegrationKyriba’s Connectivity-as-a-Service (CaaS) accelerates the process of connecting your ERP systems to your banking partners, relieving potential development and maintenance burdens on IT. With one API gateway, clients can connect via Kyriba to over 1,000 global banks, supported by an extensive format library of 50,000 pre-developed and pre-tested payment scenarios.Read the fact sheet

Fact SheetsKyriba Oracle Cloud API IntegrationKyriba’s Connectivity-as-a-Service (CaaS) accelerates the process of connecting your ERP systems to your banking partners, relieving potential development and maintenance burdens on IT. With one API gateway, clients can connect via Kyriba to over 1,000 global banks, supported by an extensive format library of 50,000 pre-developed and pre-tested payment scenarios.Read the fact sheet -

eBooks, Thought LeadershipCFOs Guide to Reducing the Risk of FraudBusiness Email Compromise BEC scams, in which fraudsters send emails to employees pretending to be the CFO or CEO, are becoming increasingly common. Other attacks prey on weak user authentication procedures to gain access to essential systems.Read the eBook

eBooks, Thought LeadershipCFOs Guide to Reducing the Risk of FraudBusiness Email Compromise BEC scams, in which fraudsters send emails to employees pretending to be the CFO or CEO, are becoming increasingly common. Other attacks prey on weak user authentication procedures to gain access to essential systems.Read the eBook -

eBooks, Thought LeadershipAFP Executive Guide: Rethinking Liquidity Planning to Manage the Cash LifecycleWith the use of APIs, artificial intelligence (AI) and data analytics, cash forecasting is evolving into a more proactive liquidity planning process. Kyriba is proud to be a supporter of the AFP Executive Guide...Read the eBook

eBooks, Thought LeadershipAFP Executive Guide: Rethinking Liquidity Planning to Manage the Cash LifecycleWith the use of APIs, artificial intelligence (AI) and data analytics, cash forecasting is evolving into a more proactive liquidity planning process. Kyriba is proud to be a supporter of the AFP Executive Guide...Read the eBook -

VideosKyriba Payments: Streamlining Your Payments Process with Security and EfficiencyAs the world’s most connected enterprise liquidity management platform, Kyriba offers unparalleled cloud-based SaaS solutions via Connectivity-as-a-Service (CaaS).Watch the video

VideosKyriba Payments: Streamlining Your Payments Process with Security and EfficiencyAs the world’s most connected enterprise liquidity management platform, Kyriba offers unparalleled cloud-based SaaS solutions via Connectivity-as-a-Service (CaaS).Watch the video -

VideosKyriba Risk Management: Three Steps to Reduce VolatilityKyriba’s Risk Management minimizes the effects of market fluctuations on revenue, earnings and balance sheets.Watch the video

VideosKyriba Risk Management: Three Steps to Reduce VolatilityKyriba’s Risk Management minimizes the effects of market fluctuations on revenue, earnings and balance sheets.Watch the video -

VideosKyriba’s Integrated Treasury SolutionsWatch this Kyriba Treasury product video to learn how Kyriba’s treasury management solutions can enhance your treasury operations.Watch the video

VideosKyriba’s Integrated Treasury SolutionsWatch this Kyriba Treasury product video to learn how Kyriba’s treasury management solutions can enhance your treasury operations.Watch the video -

VideosKyriba Working Capital: Empowering CFOs to Unlock LiquidityWatch this Kyriba Working Capital product video to learn how Kyriba's Working Capital solutions empower CFOs to unlock liquidityWatch the video

VideosKyriba Working Capital: Empowering CFOs to Unlock LiquidityWatch this Kyriba Working Capital product video to learn how Kyriba's Working Capital solutions empower CFOs to unlock liquidityWatch the video -

VideosKyriba Connectivity-as-a-Service: Accelerate Your ERP Bank ConnectivityAs the world’s most connected enterprise liquidity management platform, Kyriba offers unparalleled cloud-based SaaS solutions via Connectivity-as-a-Service (CaaS).Watch the video

VideosKyriba Connectivity-as-a-Service: Accelerate Your ERP Bank ConnectivityAs the world’s most connected enterprise liquidity management platform, Kyriba offers unparalleled cloud-based SaaS solutions via Connectivity-as-a-Service (CaaS).Watch the video -

FAQsWhat are Bank Reporting and Payment Formats?Bank reporting and payment formats exchange payment instructions and reporting information between banks and their clients.Read More

FAQsWhat are Bank Reporting and Payment Formats?Bank reporting and payment formats exchange payment instructions and reporting information between banks and their clients.Read More -

WebinarsNavigating the Future: Bank Connectivity, Cloud Migration, and Instant PaymentsJoin Deloitte and Kyriba to learn about the future of payments. Discover important topics to show where the market is likely headed so you can better understand and navigate the changes ahead.View Recording

WebinarsNavigating the Future: Bank Connectivity, Cloud Migration, and Instant PaymentsJoin Deloitte and Kyriba to learn about the future of payments. Discover important topics to show where the market is likely headed so you can better understand and navigate the changes ahead.View Recording -

eBooks, Thought LeadershipFive Payment Catastrophes to AvoidA Kyriba Guide to Corporate Payment Workflows An efficient and secure corporate payment workflow is the backbone of a successful modern enterprise. Every financial transaction – from routine supplier payments to critical intercontinental transfers...Read the eBook

eBooks, Thought LeadershipFive Payment Catastrophes to AvoidA Kyriba Guide to Corporate Payment Workflows An efficient and secure corporate payment workflow is the backbone of a successful modern enterprise. Every financial transaction – from routine supplier payments to critical intercontinental transfers...Read the eBook -

Thought Leadership, eBooksPioneering Real-time Global Banking ConnectivityBank API Best Practices for Bank Partners For two decades, Kyriba has forged a reputation as the industry's frontrunner in corporate-to-bank Connectivity-as-a-Service. With robust integrations with 1000+ global banks, Kyriba is the world's most...Learn more

Thought Leadership, eBooksPioneering Real-time Global Banking ConnectivityBank API Best Practices for Bank Partners For two decades, Kyriba has forged a reputation as the industry's frontrunner in corporate-to-bank Connectivity-as-a-Service. With robust integrations with 1000+ global banks, Kyriba is the world's most...Learn more -

WebinarsThe Liquidity Pulse – Headlines That Impact The Lifeblood of BusinessAre you ready to stay ahead of the curve in the ever-evolving world of finance? In the fast-paced world of finance, staying informed is crucial. Join us for The Liquidity Pulse, where industry experts...View Recording

WebinarsThe Liquidity Pulse – Headlines That Impact The Lifeblood of BusinessAre you ready to stay ahead of the curve in the ever-evolving world of finance? In the fast-paced world of finance, staying informed is crucial. Join us for The Liquidity Pulse, where industry experts...View Recording -

Success StoriesCondé Nast’s Transformation Overhauls Liquidity, Bank Relationships and Treasury TechCondé Nast’s (CN) treasury team identified several challenges in its effort to support the company build a new global organisational structure. Like the need to improve inefficient payment processes around inconsistent processing across markets and low levels of automation.Read the success story

Success StoriesCondé Nast’s Transformation Overhauls Liquidity, Bank Relationships and Treasury TechCondé Nast’s (CN) treasury team identified several challenges in its effort to support the company build a new global organisational structure. Like the need to improve inefficient payment processes around inconsistent processing across markets and low levels of automation.Read the success story -

Success StoriesClearsulting Partnership Elevates Treasury AgilityClearsulting’s partnership with Kyriba offers a comprehensive suite of services designed to elevate your treasury function. Through meticulous analysis, Clearsulting identifies pain points and inefficiencies within your organization’s current treasury operations and paves the way for tailored enhancements and streamlined processes. The collaboration isn’t just about treasury technology implementation; it’s about embracing Kyriba as a catalyst for change.Read the success story

Success StoriesClearsulting Partnership Elevates Treasury AgilityClearsulting’s partnership with Kyriba offers a comprehensive suite of services designed to elevate your treasury function. Through meticulous analysis, Clearsulting identifies pain points and inefficiencies within your organization’s current treasury operations and paves the way for tailored enhancements and streamlined processes. The collaboration isn’t just about treasury technology implementation; it’s about embracing Kyriba as a catalyst for change.Read the success story -

Success StoriesBally’s Leverage APIs and Cloud to Deliver SolutionHighly Commended Winner Best Emerging Technology Solution The Challenge One of Bally’s key providers of payment services is FreemarketFX with a connectivity strategy that mandates use of a REST API for statement reporting and...Read the success story

Success StoriesBally’s Leverage APIs and Cloud to Deliver SolutionHighly Commended Winner Best Emerging Technology Solution The Challenge One of Bally’s key providers of payment services is FreemarketFX with a connectivity strategy that mandates use of a REST API for statement reporting and...Read the success story -

Success StoriesAmazon ‘Thinks Big’ with Machine Learning Forecasting SolutionOverall Winner Best Cash Flow Forecasting Solution The Challenge Think Big is a key leadership principle at Amazon, and the team knows how important it is to manage its capital structure efficiently at scale....Read the success story

Success StoriesAmazon ‘Thinks Big’ with Machine Learning Forecasting SolutionOverall Winner Best Cash Flow Forecasting Solution The Challenge Think Big is a key leadership principle at Amazon, and the team knows how important it is to manage its capital structure efficiently at scale....Read the success story -

Success StoriesViatris Addressed a Complex FX Environment with an Impressive Technology SolutionOverall Winner Best Foreign Exchange Solution The Challenge Following its formation, the company faced a complex FX environment. FX risk management was performed separately at legacy Mylan and legacy Upjohn entities with each process...Read the success story

Success StoriesViatris Addressed a Complex FX Environment with an Impressive Technology SolutionOverall Winner Best Foreign Exchange Solution The Challenge Following its formation, the company faced a complex FX environment. FX risk management was performed separately at legacy Mylan and legacy Upjohn entities with each process...Read the success story -

Fact Sheets, Mid-Market ResourcesKyriba NetSuite API IntegrationKyriba’s Connectivity-as-a-Service (CaaS) accelerates this process and relieves potential development and maintenance burdens on IT. With one API gateway, clients can connect via Kyriba to over 1,000 global banks, supported by an extensive format library of 50,000 pre-developed and pre-tested payment scenarios.Read the fact sheet

Fact Sheets, Mid-Market ResourcesKyriba NetSuite API IntegrationKyriba’s Connectivity-as-a-Service (CaaS) accelerates this process and relieves potential development and maintenance burdens on IT. With one API gateway, clients can connect via Kyriba to over 1,000 global banks, supported by an extensive format library of 50,000 pre-developed and pre-tested payment scenarios.Read the fact sheet -

WebinarsRecession ahead? Impact on Corporate Liquidity from the Student Debt UnfreezeThink your business is safe from the effects of lifting the student loan payment pause? Think again.View Recording

WebinarsRecession ahead? Impact on Corporate Liquidity from the Student Debt UnfreezeThink your business is safe from the effects of lifting the student loan payment pause? Think again.View Recording -

eBooks, Thought LeadershipThe Perfect Storm of B2B Payment Fraud: How to Defend Your Treasury Before It’s Too LateB2B payment fraud is one of the top concerns keeping CFOs and treasurers up at night, having increased in importance due to the proliferation of spear-phishing, data breaches and the resulting loss in company...Read the eBook

eBooks, Thought LeadershipThe Perfect Storm of B2B Payment Fraud: How to Defend Your Treasury Before It’s Too LateB2B payment fraud is one of the top concerns keeping CFOs and treasurers up at night, having increased in importance due to the proliferation of spear-phishing, data breaches and the resulting loss in company...Read the eBook -

eBooks, Thought LeadershipFive Questions Every Modern CFO Should Ask to Maximize GrowthDiscover key strategies and insights for modern CFOs to unlock the potential through effective cash and risk management to maximize growth and profitability.Read the eBook

eBooks, Thought LeadershipFive Questions Every Modern CFO Should Ask to Maximize GrowthDiscover key strategies and insights for modern CFOs to unlock the potential through effective cash and risk management to maximize growth and profitability.Read the eBook -

WebinarsFX Value at Risk SolutionsJoin us to get introduced to the powerful set of Value at Risk Based Analytics and Hedging Solutions within Kyriba’s FX Solution Suite for Balance Sheet Exposure Management.View Recording

WebinarsFX Value at Risk SolutionsJoin us to get introduced to the powerful set of Value at Risk Based Analytics and Hedging Solutions within Kyriba’s FX Solution Suite for Balance Sheet Exposure Management.View Recording -

WebinarsFX Value at Risk FundamentalsJoin FX Experts Andy Gage and Jeff Goggins in the insights packed session on how to apply Value at Risk analysis concepts within modern FX risk management programs. These concepts can enable FX managers...View Recording

WebinarsFX Value at Risk FundamentalsJoin FX Experts Andy Gage and Jeff Goggins in the insights packed session on how to apply Value at Risk analysis concepts within modern FX risk management programs. These concepts can enable FX managers...View Recording -

WebinarsKyriba Demo WebinarWednesday, August 16th | 10:00am SGT | Find out how Kyriba has elevated technology for CFOs and Treasurers around the world. Take a deep dive into the Kyriba Enterprise Liquidity Management platform as we...View Recording

WebinarsKyriba Demo WebinarWednesday, August 16th | 10:00am SGT | Find out how Kyriba has elevated technology for CFOs and Treasurers around the world. Take a deep dive into the Kyriba Enterprise Liquidity Management platform as we...View Recording -

eBooks, Thought LeadershipFive Strategies for Treasurers Amid Economic VolatilityIn today’s highly volatile economic landscape, treasurers are confronted with a new set of challenges, including soaring global inflation, elevated interest rates and an uncertain economic outlook. These obstacles significantly impact financial decision-making and require CFOs and treasurers to devise robust strategies to tackle them effectively.Read the eBook

eBooks, Thought LeadershipFive Strategies for Treasurers Amid Economic VolatilityIn today’s highly volatile economic landscape, treasurers are confronted with a new set of challenges, including soaring global inflation, elevated interest rates and an uncertain economic outlook. These obstacles significantly impact financial decision-making and require CFOs and treasurers to devise robust strategies to tackle them effectively.Read the eBook -

eBooks, Thought LeadershipImproving Efficiency and Reducing Fraud through Payments Hubs: A 15-minute Quick GuideImproving Efficiency and Reducing Fraud through Payments Hubs: A 15-minute Quick GuideRead the eBook

eBooks, Thought LeadershipImproving Efficiency and Reducing Fraud through Payments Hubs: A 15-minute Quick GuideImproving Efficiency and Reducing Fraud through Payments Hubs: A 15-minute Quick GuideRead the eBook -

Research, Thought LeadershipIDC MarketScape: Worldwide SaaS and Cloud-Enabled Enterprise Treasury and Risk Management Applications 2023 Vendor AssessmentThe IDC MarketScape: Worldwide SaaS and Cloud-Enabled Enterprise Treasury and Risk Management Applications 2023 Vendor Assessment underscores the crucial role of effective liquidity management. The report highlights liquidity ratios as vital indicators of financial...Read the Report

Research, Thought LeadershipIDC MarketScape: Worldwide SaaS and Cloud-Enabled Enterprise Treasury and Risk Management Applications 2023 Vendor AssessmentThe IDC MarketScape: Worldwide SaaS and Cloud-Enabled Enterprise Treasury and Risk Management Applications 2023 Vendor Assessment underscores the crucial role of effective liquidity management. The report highlights liquidity ratios as vital indicators of financial...Read the Report -

WebinarsKyriba Demo Webinar Series: Bank Connectivity as a ServiceKyriba connects to over 1,000 banks and more than 10,000 ERP instances, delivering the largest global network for ERP-to-bank connectivity. As one client recently put it, "we aren't in the payment formatting business nor...View Recording

WebinarsKyriba Demo Webinar Series: Bank Connectivity as a ServiceKyriba connects to over 1,000 banks and more than 10,000 ERP instances, delivering the largest global network for ERP-to-bank connectivity. As one client recently put it, "we aren't in the payment formatting business nor...View Recording -

Webinars5 Steps to Avoid a Payments CatastropheConnecting your ERP(s) to your banks became a lot more complicated with the launch of FedNow, cross-border instant payment networks, the migration to XML ISO20022 formats and the need to inject AI into your...View Recording

Webinars5 Steps to Avoid a Payments CatastropheConnecting your ERP(s) to your banks became a lot more complicated with the launch of FedNow, cross-border instant payment networks, the migration to XML ISO20022 formats and the need to inject AI into your...View Recording -

Research, Currency Impact ReportsKyriba’s July 2023 Currency Impact ReportKyriba’s Currency Impact Report (CIR), a comprehensive quarterly report which details the impacts of foreign exchange (FX) exposures among 1,200 multinational companies based in North America and Europe with at least 15 percent of their revenue coming from overseas, sustained $49.09 billion in total impacts to earnings from currency volatility.Read the Report

Research, Currency Impact ReportsKyriba’s July 2023 Currency Impact ReportKyriba’s Currency Impact Report (CIR), a comprehensive quarterly report which details the impacts of foreign exchange (FX) exposures among 1,200 multinational companies based in North America and Europe with at least 15 percent of their revenue coming from overseas, sustained $49.09 billion in total impacts to earnings from currency volatility.Read the Report -

Success StoriesKodak Excels with Automated Treasury ReportingPrior to adopting and implementing Kyriba globally, the teams at Kodak were unable to provide senior leadership with a snapshot of their daily global cash balances. Simply looking at the bank balances did not...Read the success story

Success StoriesKodak Excels with Automated Treasury ReportingPrior to adopting and implementing Kyriba globally, the teams at Kodak were unable to provide senior leadership with a snapshot of their daily global cash balances. Simply looking at the bank balances did not...Read the success story -

eBooks, Thought LeadershipInternational Treasury Centers Unlock Global Cash VisibilityDuring the pandemic, most organizations have experienced unexpected fluctuations in their cash and liquidity levels due to the volatile, unsettled global economy. Treasury operating models have a direct correlation to how well cash positioning and liquidity forecasting is delivered and executed.Read the eBook

eBooks, Thought LeadershipInternational Treasury Centers Unlock Global Cash VisibilityDuring the pandemic, most organizations have experienced unexpected fluctuations in their cash and liquidity levels due to the volatile, unsettled global economy. Treasury operating models have a direct correlation to how well cash positioning and liquidity forecasting is delivered and executed.Read the eBook -

eBooks, Thought LeadershipNavigating Financial Flux: CFOs Perspective on Strategic Treasury ManagementWhile corporates have enjoyed an unprecedented financial boom for years, the recent volatility in the global markets is an indicator of changing times that could bring sharply rising interest rates and the end of cheap money. The recent demise of Silicon Valley Bank is a wake-up call to the purpose of capital and liquidity requirements and the importance of strategic treasury management.Read the eBook

eBooks, Thought LeadershipNavigating Financial Flux: CFOs Perspective on Strategic Treasury ManagementWhile corporates have enjoyed an unprecedented financial boom for years, the recent volatility in the global markets is an indicator of changing times that could bring sharply rising interest rates and the end of cheap money. The recent demise of Silicon Valley Bank is a wake-up call to the purpose of capital and liquidity requirements and the importance of strategic treasury management.Read the eBook -

Fact SheetsKyriba SAP IntegrationUnleash the Power of Enterprise Liquidity Management with SAP and Kyriba: The certified Kyriba SAP integration, including SFTP and API integration, seamlessly connects SAP with Kyriba to automate the workflow between the two platforms.Read the fact sheet

Fact SheetsKyriba SAP IntegrationUnleash the Power of Enterprise Liquidity Management with SAP and Kyriba: The certified Kyriba SAP integration, including SFTP and API integration, seamlessly connects SAP with Kyriba to automate the workflow between the two platforms.Read the fact sheet -

Fact SheetsKyriba & Goldman Sachs Asset Management MosaicExpanding Investment Options for Treasurers to Increase Return on Surplus Liquidity Kyriba’s Treasury Management System now connects with Goldman Sachs Liquidity Solutions Platform, Mosaic, expanding options for treasurers and increasing ways to keep surplus...Read the fact sheet

Fact SheetsKyriba & Goldman Sachs Asset Management MosaicExpanding Investment Options for Treasurers to Increase Return on Surplus Liquidity Kyriba’s Treasury Management System now connects with Goldman Sachs Liquidity Solutions Platform, Mosaic, expanding options for treasurers and increasing ways to keep surplus...Read the fact sheet -

WebinarsLiquidity Planning Demo: Key to Real-time Decision SupportTuesday, July 4th | 10:00 am SGT Find out how Kyriba’s Cash Management, Liquidity Planning and Liquidity Analytics modules enables treasury teams and finance leaders in treasury to proactively manage cash and liquidity lifecycles...View Recording

WebinarsLiquidity Planning Demo: Key to Real-time Decision SupportTuesday, July 4th | 10:00 am SGT Find out how Kyriba’s Cash Management, Liquidity Planning and Liquidity Analytics modules enables treasury teams and finance leaders in treasury to proactively manage cash and liquidity lifecycles...View Recording -

WebinarsLiquidity Planning Demo: Optimizing Cash and Liquidity in KyribaA showcase of Kyriba's cash and liquidity management capabilities. Our presentation team will demonstrate how Kyriba clients use our platform to transform their approach to cash and liquidity planning.View Recording

WebinarsLiquidity Planning Demo: Optimizing Cash and Liquidity in KyribaA showcase of Kyriba's cash and liquidity management capabilities. Our presentation team will demonstrate how Kyriba clients use our platform to transform their approach to cash and liquidity planning.View Recording -

WebinarsTop 3 Cash Flow Mistakes Every Treasury MakesThe cash forecast is once again the most critical tool connecting treasury with corporate strategy and board-level decisions. Companies are expected to increase cash flow and drive a greater return on cash in this...View Recording

WebinarsTop 3 Cash Flow Mistakes Every Treasury MakesThe cash forecast is once again the most critical tool connecting treasury with corporate strategy and board-level decisions. Companies are expected to increase cash flow and drive a greater return on cash in this...View Recording -

Success StoriesRSM Partnership Delivers Treasury Operation Success at CSIG and MoreRSM US LLP is continuing to invest in its treasury operation and is a premier partner to the Kyriba organization. RSM is the fifth largest audit, tax, and consulting firm in the United States...Read the success story

Success StoriesRSM Partnership Delivers Treasury Operation Success at CSIG and MoreRSM US LLP is continuing to invest in its treasury operation and is a premier partner to the Kyriba organization. RSM is the fifth largest audit, tax, and consulting firm in the United States...Read the success story -

eBooks, Thought LeadershipCentralizing Payments with an In-House Bank to Fully Optimize Working CapitalModern treasury teams have numerous available tools and structures to succeed in today’s global economy. With supply chain disruptions and decreased cash flows prevalent, treasury can leverage an in-house bank (IHB) and Payments Hub...Read the eBook

eBooks, Thought LeadershipCentralizing Payments with an In-House Bank to Fully Optimize Working CapitalModern treasury teams have numerous available tools and structures to succeed in today’s global economy. With supply chain disruptions and decreased cash flows prevalent, treasury can leverage an in-house bank (IHB) and Payments Hub...Read the eBook -

Success StoriesSabre, Varsity Brands, CHFA and International Seaways: Treasury Success with Elire and KyribaElire is a Kyriba Platinum Plus Partner with over 18 years of experience helping clients implement successful Treasury Management Solutions. With an experienced team of over 20 Treasury Consultants across multiple Treasury disciplines and...Read the success story

Success StoriesSabre, Varsity Brands, CHFA and International Seaways: Treasury Success with Elire and KyribaElire is a Kyriba Platinum Plus Partner with over 18 years of experience helping clients implement successful Treasury Management Solutions. With an experienced team of over 20 Treasury Consultants across multiple Treasury disciplines and...Read the success story -

WebinarsCash Forecasting 2.0: The Emergence of Liquidity PlanningThe CFO no longer cares about your cash forecast! They need more. CFOs are focused on meeting free cash flow targets and require real-time insight to proactively manage liquidity across the enterprise to reduce...View Recording

WebinarsCash Forecasting 2.0: The Emergence of Liquidity PlanningThe CFO no longer cares about your cash forecast! They need more. CFOs are focused on meeting free cash flow targets and require real-time insight to proactively manage liquidity across the enterprise to reduce...View Recording -

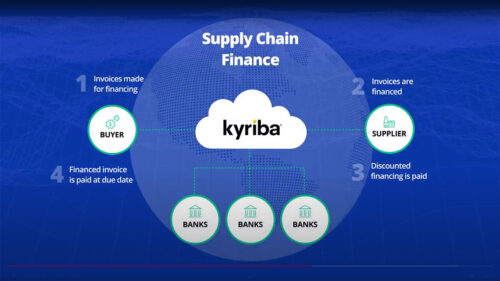

eBooks, Thought LeadershipVolatile Times Require Effective Working Capital SolutionsIn this e-book, you will gain an understanding of how supply chain finance (SCF), dynamic discounting and receivables finance can create a win-win solution for both buyers and suppliers while enabling treasury and procurement to work hand-in-hand to deliver working capital improvements.Read the eBook

eBooks, Thought LeadershipVolatile Times Require Effective Working Capital SolutionsIn this e-book, you will gain an understanding of how supply chain finance (SCF), dynamic discounting and receivables finance can create a win-win solution for both buyers and suppliers while enabling treasury and procurement to work hand-in-hand to deliver working capital improvements.Read the eBook -

Videos, Success StoriesAFP 2022: Kyriba Client Testimonials for Enterprise Liquidity ManagementOrganizations from many industries and of various sizes have embraced Kyriba for their enterprise liquidity management needs. At AFP’s annual conference, our team set up a testimonial station at our convention booth, where clients...Watch the video

Videos, Success StoriesAFP 2022: Kyriba Client Testimonials for Enterprise Liquidity ManagementOrganizations from many industries and of various sizes have embraced Kyriba for their enterprise liquidity management needs. At AFP’s annual conference, our team set up a testimonial station at our convention booth, where clients...Watch the video -

Success StoriesFilmRise: Implementation of the Year Award Runner UpAwarded to the company that had a clear project plan, stuck to it, and maintained the project discipline to achieve a go-live date with great success. Nominated by 3PO Consulting.Read the success story

Success StoriesFilmRise: Implementation of the Year Award Runner UpAwarded to the company that had a clear project plan, stuck to it, and maintained the project discipline to achieve a go-live date with great success. Nominated by 3PO Consulting.Read the success story -

Success StoriesOrix: Fraud and Compliance Masters Award WinnerRecognizing best-in-class performance in payments fraud solution and compliance management.Read the success story

Success StoriesOrix: Fraud and Compliance Masters Award WinnerRecognizing best-in-class performance in payments fraud solution and compliance management.Read the success story -

eBooks, Thought LeadershipAccelerating Your Business with Compelling Real-Time Payments Use Cases for Treasury and FinanceMaking Real-Time Payments a Reality for Finance and Treasury

eBooks, Thought LeadershipAccelerating Your Business with Compelling Real-Time Payments Use Cases for Treasury and FinanceMaking Real-Time Payments a Reality for Finance and Treasury

Real-time payments initiatives are proliferating all over the globe and while many countries have jumped on the bandwagon with various real-time payments use cases, corporate adoption has lagged. But to build the business case for implementing real- time, treasury and finance departments need to identify more business relevant use cases.Read the eBook -

Success StoriesWilliams-Sonoma: Achievements in Productivity Award Runner-upAwarded to the company that has posted significant gains in productivity, freeing up treasury's time to focus on more strategic initiatives. Nominated by 3PO.Read the success story

Success StoriesWilliams-Sonoma: Achievements in Productivity Award Runner-upAwarded to the company that has posted significant gains in productivity, freeing up treasury's time to focus on more strategic initiatives. Nominated by 3PO.Read the success story -

Success StoriesWarner Bros. Discovery: Implementation of the Year Award WinnerAwarded to the company that had a clear TMS implementation project plan, stuck to it, and maintained the project discipline to achieve a go-live date with great success. Nominated by Actualize Consulting.Read the success story

Success StoriesWarner Bros. Discovery: Implementation of the Year Award WinnerAwarded to the company that had a clear TMS implementation project plan, stuck to it, and maintained the project discipline to achieve a go-live date with great success. Nominated by Actualize Consulting.Read the success story -

WebinarsDemo Series: FX Cash Flow & Back Office DemoTuesday, June 13th | 11:00am ET | 8:00am PT | With increased foreign exchange volatility expected to continue for the foreseeable future combined with rising hedging costs, FX Risk Management is proving to be...View Recording

WebinarsDemo Series: FX Cash Flow & Back Office DemoTuesday, June 13th | 11:00am ET | 8:00am PT | With increased foreign exchange volatility expected to continue for the foreseeable future combined with rising hedging costs, FX Risk Management is proving to be...View Recording -

WebinarsAmerican Honda, Improving Liquidity Management with Kyriba & ICDWith continued uncertainty in financial markets and the economy, managing liquidity and diversifying cash investments is top of mind for many treasury professionals. In this webinar, American Honda shares how they use Kyriba’s ICD...View Recording

WebinarsAmerican Honda, Improving Liquidity Management with Kyriba & ICDWith continued uncertainty in financial markets and the economy, managing liquidity and diversifying cash investments is top of mind for many treasury professionals. In this webinar, American Honda shares how they use Kyriba’s ICD...View Recording -

Research, Currency Impact ReportsKyriba’s May 2023 Currency Impact ReportKyriba’s Currency Impact Report (CIR), a comprehensive quarterly report which details the impacts of foreign exchange (FX) exposures among 1,200 multinational companies based in North America and Europe with at least 15 percent of their revenue coming from overseas, sustained $49.09 billion in total impacts to earnings from currency volatility.Read the Report

Research, Currency Impact ReportsKyriba’s May 2023 Currency Impact ReportKyriba’s Currency Impact Report (CIR), a comprehensive quarterly report which details the impacts of foreign exchange (FX) exposures among 1,200 multinational companies based in North America and Europe with at least 15 percent of their revenue coming from overseas, sustained $49.09 billion in total impacts to earnings from currency volatility.Read the Report -

FAQsWhat is Receivables Finance?Receivables finance, also known as invoice finance, is a type of working capital facility that enables businesses to borrow against unpaid invoices. Receivables finance helps businesses to improve their cash flow by unlocking the value of invoices they’ve already issued, allowing them to access funds immediately instead of waiting for their customers to pay.Read More

FAQsWhat is Receivables Finance?Receivables finance, also known as invoice finance, is a type of working capital facility that enables businesses to borrow against unpaid invoices. Receivables finance helps businesses to improve their cash flow by unlocking the value of invoices they’ve already issued, allowing them to access funds immediately instead of waiting for their customers to pay.Read More -

Success StoriesNew York Life Investments: Payments Innovator Award WinnerAwarded to the company that has minimized fraud, standardized and streamlined payment processes.Read the success story

Success StoriesNew York Life Investments: Payments Innovator Award WinnerAwarded to the company that has minimized fraud, standardized and streamlined payment processes.Read the success story -

Success StoriesCostco and Phillips 66: Treasury Operations Client Success Award WinnersChosen by Kyriba's Client Success Team for best-in-class performance across treasury operations.Read the success story

Success StoriesCostco and Phillips 66: Treasury Operations Client Success Award WinnersChosen by Kyriba's Client Success Team for best-in-class performance across treasury operations.Read the success story -

Success StoriesNucor: Payments Innovator Award WinnerAwarded to the company that has minimized fraud, standardized and streamlined check payment processing. Nominated by 3PO Consulting.Read the success story

Success StoriesNucor: Payments Innovator Award WinnerAwarded to the company that has minimized fraud, standardized and streamlined check payment processing. Nominated by 3PO Consulting.Read the success story -

FAQsWhat is Treasury Data Analytics?Treasury data analytics is the practice of using data analysis techniques to gain insights into a company’s treasury operations, including cash and liquidity management, investment portfolios, risk management, and supply chain finance. Treasury data...Read More

FAQsWhat is Treasury Data Analytics?Treasury data analytics is the practice of using data analysis techniques to gain insights into a company’s treasury operations, including cash and liquidity management, investment portfolios, risk management, and supply chain finance. Treasury data...Read More -

Success StoriesHF Sinclair: Treasury Transformation Award WinnerAwarded to the company that embraced technology for optimal transformation and efficiency of their treasury department.Read the success story

Success StoriesHF Sinclair: Treasury Transformation Award WinnerAwarded to the company that embraced technology for optimal transformation and efficiency of their treasury department.Read the success story -

Success StoriesCharter Communications: Winner of Achievements in Productivity AwardAwarded to the company that has posted significant gains in productivity by creating fully automated cash and investment workflow, freeing up treasury's time to focus on more strategic initiatives. Nominated by ICD.Read the success story

Success StoriesCharter Communications: Winner of Achievements in Productivity AwardAwarded to the company that has posted significant gains in productivity by creating fully automated cash and investment workflow, freeing up treasury's time to focus on more strategic initiatives. Nominated by ICD.Read the success story -

Success StoriesOtis: FX Optimization Award Runner UpThis award, sponsored by Kyriba partner and client Oanda, honors the company that has embraced Kyriba's FX module, and made great strides in managing FX exposure and risk.Read the success story

Success StoriesOtis: FX Optimization Award Runner UpThis award, sponsored by Kyriba partner and client Oanda, honors the company that has embraced Kyriba's FX module, and made great strides in managing FX exposure and risk.Read the success story -

Success StoriesMetLife: Fraud and Compliance Masters Award WinnerRecognizing best-in-class performance in payments fraud prevention and compliance management.Read the success story

Success StoriesMetLife: Fraud and Compliance Masters Award WinnerRecognizing best-in-class performance in payments fraud prevention and compliance management.Read the success story -

WebinarsLiquidity Planning Demo: Real-time Decision Support – KyribaMay 18 | 11:00am SGT | Join Kyriba on 18th May 2023 at 11am SG time and find out how Kyriba’s Cash Management, Liquidity Planning and Liquidity Analytics modules enables treasury teams and finance...View Recording

WebinarsLiquidity Planning Demo: Real-time Decision Support – KyribaMay 18 | 11:00am SGT | Join Kyriba on 18th May 2023 at 11am SG time and find out how Kyriba’s Cash Management, Liquidity Planning and Liquidity Analytics modules enables treasury teams and finance...View Recording -

Success StoriesNational Veterinary Associates: Treasury Transformation Award Runner-UpAwarded to the company that embraced technology for optimal transformation and efficiency of their treasury department. Nominated by Elire and PWC.Read the success story

Success StoriesNational Veterinary Associates: Treasury Transformation Award Runner-UpAwarded to the company that embraced technology for optimal transformation and efficiency of their treasury department. Nominated by Elire and PWC.Read the success story -

eBooks, Thought LeadershipWhy Digitalized Bank Connectivity is the Key to Optimizing Cash DeploymentCompanies that can identify and use cash with confidence can now leverage liquidity as an asset for strategic value creation. It’s a competitive advantage that has often been overlooked, or not available, but which...Read the eBook

eBooks, Thought LeadershipWhy Digitalized Bank Connectivity is the Key to Optimizing Cash DeploymentCompanies that can identify and use cash with confidence can now leverage liquidity as an asset for strategic value creation. It’s a competitive advantage that has often been overlooked, or not available, but which...Read the eBook -

KyribaLive 2023 Recorded SessionsKyribaLive is where treasury and finance leaders engage, connect and transform. See all the recorded sessions.Read More

KyribaLive 2023 Recorded SessionsKyribaLive is where treasury and finance leaders engage, connect and transform. See all the recorded sessions.Read More -

Success StoriesEastman Chemical: FX Optimization Award WinnerThis award, sponsored by Kyriba partner and client Oanda, honors the company that has embraced Kyriba's FX module, and made great strides in managing FX exposure and risk.Read the success story

Success StoriesEastman Chemical: FX Optimization Award WinnerThis award, sponsored by Kyriba partner and client Oanda, honors the company that has embraced Kyriba's FX module, and made great strides in managing FX exposure and risk.Read the success story -

FAQsWhat is Cash Forecasting?Cash forecasting is the process of predicting near future cash flows, including both inflows and outflows, based on current business conditions and past performance. It is a crucial component of effective cash and liquidity...Read More

FAQsWhat is Cash Forecasting?Cash forecasting is the process of predicting near future cash flows, including both inflows and outflows, based on current business conditions and past performance. It is a crucial component of effective cash and liquidity...Read More -

eBooks, Thought LeadershipBest Practices for Designing Your Treasury Management SystemDownload this ebook to learn how you can prepare your team for a successful implementation and achieve the most value from your TMS.Read the eBook

eBooks, Thought LeadershipBest Practices for Designing Your Treasury Management SystemDownload this ebook to learn how you can prepare your team for a successful implementation and achieve the most value from your TMS.Read the eBook -

Fact SheetsKyriba and U.S. Bank Enable APIs for Real-time TreasuryModern APIs to pay, get payment confirmation, and get account balance, all in real-time. As part of a strategic partnership Kyriba and U.S. Bank have developed API connectors to drive real-time treasury, making real-time...Read the fact sheet

Fact SheetsKyriba and U.S. Bank Enable APIs for Real-time TreasuryModern APIs to pay, get payment confirmation, and get account balance, all in real-time. As part of a strategic partnership Kyriba and U.S. Bank have developed API connectors to drive real-time treasury, making real-time...Read the fact sheet -

Research, Thought Leadership2022 Strategic Treasurer Treasury Technology Analyst Report2022 Strategic Treasurer Treasury Technology Analyst ReportRead the Report

Research, Thought Leadership2022 Strategic Treasurer Treasury Technology Analyst Report2022 Strategic Treasurer Treasury Technology Analyst ReportRead the Report -

Fact SheetsFX Exposure Management for OracleDelivering on-demand interactivity with Oracle applications, Kyriba for Oracle is a cloud-based solution that reduces the risk of foreign currency volatility to earnings per share and corporate value. The Cloud-based Business Model Advantage: Quick...Read the fact sheet

Fact SheetsFX Exposure Management for OracleDelivering on-demand interactivity with Oracle applications, Kyriba for Oracle is a cloud-based solution that reduces the risk of foreign currency volatility to earnings per share and corporate value. The Cloud-based Business Model Advantage: Quick...Read the fact sheet -

FAQsWhat are APIs in Treasury?Application Programming Interface (API) is an interface provided by one application for other application(s) to communicate with it. APIs in treasury management software connect different systems to share cash data or execute cash management...Read More

FAQsWhat are APIs in Treasury?Application Programming Interface (API) is an interface provided by one application for other application(s) to communicate with it. APIs in treasury management software connect different systems to share cash data or execute cash management...Read More -

Success StoriesBeam-Suntory’s Global Treasury Management Transformation: Strategic Treasury to Optimize Liquidity and Protect GrowthBeam Suntory’s Treasury transformation modernized their operations in a decentralized environment, and with the added complexity of navigating global volatility. A dispersed team challenged by manual processes with a need to leverage a system...Read the success story

Success StoriesBeam-Suntory’s Global Treasury Management Transformation: Strategic Treasury to Optimize Liquidity and Protect GrowthBeam Suntory’s Treasury transformation modernized their operations in a decentralized environment, and with the added complexity of navigating global volatility. A dispersed team challenged by manual processes with a need to leverage a system...Read the success story -

eBooks, Thought LeadershipThe Biggest FX Problem (That No One Talks About)Read the eBook

eBooks, Thought LeadershipThe Biggest FX Problem (That No One Talks About)Read the eBook -

WebinarsHow to use Treasury Technology to Overcome UncertaintyTuesday April 25 | 11:00am ET | 4:00pm GMT | Having real-time insight into the locations of your liquidity is key to survival as financial institutions begin to unravel and the world economy continues...View Recording

WebinarsHow to use Treasury Technology to Overcome UncertaintyTuesday April 25 | 11:00am ET | 4:00pm GMT | Having real-time insight into the locations of your liquidity is key to survival as financial institutions begin to unravel and the world economy continues...View Recording -

WebinarsFX Volatility Builds TMS Business CaseTuesday, May 2 | 11:00am ET | 4:00pm GMT | Securing budget for a treasury project during heightened volatility becomes easier when ROI can be achieved in months, not years. FX Risk management has...View Recording

WebinarsFX Volatility Builds TMS Business CaseTuesday, May 2 | 11:00am ET | 4:00pm GMT | Securing budget for a treasury project during heightened volatility becomes easier when ROI can be achieved in months, not years. FX Risk management has...View Recording -

Research2022 Non-Banking Financial Institutions (NBFI) Survey ResultsExecutive Summary Thank you for reading this edition of the Non-Banking Financial Institution (NBFI) Survey. This survey was underwritten by Kyriba for the 2nd year in a row as they continue to serve an...Read the Report

Research2022 Non-Banking Financial Institutions (NBFI) Survey ResultsExecutive Summary Thank you for reading this edition of the Non-Banking Financial Institution (NBFI) Survey. This survey was underwritten by Kyriba for the 2nd year in a row as they continue to serve an...Read the Report -

eBooks, Thought LeadershipUnlocking the Potential of AI in Treasury ManagementUnlocking the Potential of AI in Treasury ManagementRead the eBook

eBooks, Thought LeadershipUnlocking the Potential of AI in Treasury ManagementUnlocking the Potential of AI in Treasury ManagementRead the eBook -

WebinarsHow to Secure Project Budget During UncertaintyTuesday, April 18th | 11:00am ET | 4:00pm GMT | Securing budget for a treasury project during economic uncertainty increases the focus on defining KPIs and effectively measuring ROI. Benchmarking allows Treasurers, CFOs and...View Recording

WebinarsHow to Secure Project Budget During UncertaintyTuesday, April 18th | 11:00am ET | 4:00pm GMT | Securing budget for a treasury project during economic uncertainty increases the focus on defining KPIs and effectively measuring ROI. Benchmarking allows Treasurers, CFOs and...View Recording -

FAQsWhat is a Treasury Management System?A Treasury Management System (TMS) is a software application that allows companies to process cash flow, manage banking relationships and enhance the value of their cash flow. A Treasury Management System can help companies...Read More

FAQsWhat is a Treasury Management System?A Treasury Management System (TMS) is a software application that allows companies to process cash flow, manage banking relationships and enhance the value of their cash flow. A Treasury Management System can help companies...Read More -

ResearchGet Strategic about Liquidity Management with a Supplemental Treasury Management SystemRead the Report

ResearchGet Strategic about Liquidity Management with a Supplemental Treasury Management SystemRead the Report -

eBooks, Thought LeadershipDevelop Leading FX Risk Management Programs Through AutomationNearly every company doing business beyond its own borders faces the challenge of developing cost-effective FX risk management programs, and each year corporations incur billions of dollars in currency related losses due to global currency volatility. Even small organizations with modest international operations can be impacted by currency exposures if treasury fails to effectively manage foreign exchange (FX).Read the eBook

eBooks, Thought LeadershipDevelop Leading FX Risk Management Programs Through AutomationNearly every company doing business beyond its own borders faces the challenge of developing cost-effective FX risk management programs, and each year corporations incur billions of dollars in currency related losses due to global currency volatility. Even small organizations with modest international operations can be impacted by currency exposures if treasury fails to effectively manage foreign exchange (FX).Read the eBook -

Fact SheetsKyriba Liquidity AnalyticsKyriba’s Liquidity Analytics is part of the comprehensive SaaS-based Kyriba Analytics reporting platform giving CFOs and treasury the ability to identify enterprise-wide, integrated cash, coupled with debt and investment data presented with superior visualization...Read the fact sheet

Fact SheetsKyriba Liquidity AnalyticsKyriba’s Liquidity Analytics is part of the comprehensive SaaS-based Kyriba Analytics reporting platform giving CFOs and treasury the ability to identify enterprise-wide, integrated cash, coupled with debt and investment data presented with superior visualization...Read the fact sheet -

WebinarsDemo Series: Kyriba FX to Mitigate Currency RiskFX Risk Management is one of the most difficult objectives handed to a CFO’s organization. Touching not only all key areas of Treasury, Accounting & Finance, but also necessitating coordination with operations & lines...View Recording

WebinarsDemo Series: Kyriba FX to Mitigate Currency RiskFX Risk Management is one of the most difficult objectives handed to a CFO’s organization. Touching not only all key areas of Treasury, Accounting & Finance, but also necessitating coordination with operations & lines...View Recording -

Fact SheetsKyriba MobileKyriba Mobile securely extends core treasury and payments functions from desktops to mobile devices, allowing informed, real-time decisions on the go.Read the fact sheet

Fact SheetsKyriba MobileKyriba Mobile securely extends core treasury and payments functions from desktops to mobile devices, allowing informed, real-time decisions on the go.Read the fact sheet -

FAQsWhat is Liquidity Planning?Liquidity planning is an evolution of traditional cash forecasting surrounding the cash forecast with data which supports better-informed liquidity decisions.Read More

FAQsWhat is Liquidity Planning?Liquidity planning is an evolution of traditional cash forecasting surrounding the cash forecast with data which supports better-informed liquidity decisions.Read More -

FAQsWhat are Corporate Payments?Corporate payments, or B2B payments, usually refer to the financial transactions made by a company or corporation to pay for various expenses related to its business operations. These payments may include salaries, wages, bonuses,...Read More

FAQsWhat are Corporate Payments?Corporate payments, or B2B payments, usually refer to the financial transactions made by a company or corporation to pay for various expenses related to its business operations. These payments may include salaries, wages, bonuses,...Read More -

FAQsWhat is Open Banking for Corporates?Open banking is a banking practice that gives consumers full control over their own banking or financial data so that they can decide whether any third-party financial service providers can access the data to...Read More

FAQsWhat is Open Banking for Corporates?Open banking is a banking practice that gives consumers full control over their own banking or financial data so that they can decide whether any third-party financial service providers can access the data to...Read More -

FAQsWhat are Real-time Payments?Real-time payments are a payment type where the transmission of the payment message and the availability of “final” funds to the payee occur in real time or near-real time and on as near to...Read More

FAQsWhat are Real-time Payments?Real-time payments are a payment type where the transmission of the payment message and the availability of “final” funds to the payee occur in real time or near-real time and on as near to...Read More -

WebinarsManaging Global FX RiskFX volatility is at a 20 year high, and coupled with high interest rates, the challenge of delivering predictable earnings guidance against a tightening budget has become a top priority for CFOs.View Recording

WebinarsManaging Global FX RiskFX volatility is at a 20 year high, and coupled with high interest rates, the challenge of delivering predictable earnings guidance against a tightening budget has become a top priority for CFOs.View Recording -

Success StoriesLowe’s Uses Bank Fee Analysis to do it Right, for LessThe scale of Lowe’s bank account environment is extremely large, with over 2000 bank accounts with 33 banking partners. Prior to Kyriba, the treasury department used a third party application for bank fee analysis,...Read the success story

Success StoriesLowe’s Uses Bank Fee Analysis to do it Right, for LessThe scale of Lowe’s bank account environment is extremely large, with over 2000 bank accounts with 33 banking partners. Prior to Kyriba, the treasury department used a third party application for bank fee analysis,...Read the success story -

Webinars, Thought LeadershipKyriba Demo Webinar: On Demand, On Your Time.On-Demand, On Your Time. Kyriba has elevated technology for CFO’s and Treasurers around the world. Join us for a deep dive into the NEW Kyriba Treasury, Payments & Risk Platform. With brand new User...View Recording

Webinars, Thought LeadershipKyriba Demo Webinar: On Demand, On Your Time.On-Demand, On Your Time. Kyriba has elevated technology for CFO’s and Treasurers around the world. Join us for a deep dive into the NEW Kyriba Treasury, Payments & Risk Platform. With brand new User...View Recording -

WebinarsLiquidity Planning Demo: Thomas GavaghanIn a high interest rate environment, coupled with increasing volatility, CFOs and Treasury leaders are demanding more robust and real-time controls over their liquidity. This demo webinar will demonstrate the value of Kyriba's liquidity...View Recording

WebinarsLiquidity Planning Demo: Thomas GavaghanIn a high interest rate environment, coupled with increasing volatility, CFOs and Treasury leaders are demanding more robust and real-time controls over their liquidity. This demo webinar will demonstrate the value of Kyriba's liquidity...View Recording -

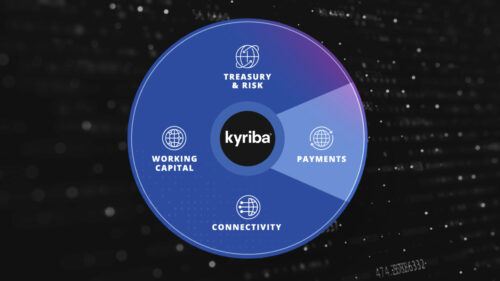

FAQsWhat is Kyriba Used for?Kyriba is the global leader in cloud treasury and finance solutions, delivering Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) for CFOs and corporate treasurers with a full suite of products and solutions across cash and risk management, payments, and working capital.Read More

FAQsWhat is Kyriba Used for?Kyriba is the global leader in cloud treasury and finance solutions, delivering Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) for CFOs and corporate treasurers with a full suite of products and solutions across cash and risk management, payments, and working capital.Read More -

What is Kyriba Used for?Kyriba is the global leader in cloud treasury and finance solutions, delivering Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) for CFOs and corporate treasurers with a full suite of products and solutions across cash and risk management, payments, and working capital.Read More

-

What is Kyriba Used for?Kyriba is the global leader in cloud treasury and finance solutions, delivering Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) for CFOs and corporate treasurers with a full suite of products and solutions across cash and risk management, payments, and working capital.Read More

-

Success StoriesOverall Winner Best Digitisation Solution DT OneTeam of Four Solve “The Big Problem” at DT One William Tan, Kyriba, Neo Zi Xin and Vincent Fu, DT One The Challenge In the past, this fast growth company faced significant operational risk...Read the success story

Success StoriesOverall Winner Best Digitisation Solution DT OneTeam of Four Solve “The Big Problem” at DT One William Tan, Kyriba, Neo Zi Xin and Vincent Fu, DT One The Challenge In the past, this fast growth company faced significant operational risk...Read the success story -